I knew the captain hadn’t made the call to switch my MOS from mortars to grunt. A clerk back in the states somewhere had done it, probably because of a glut of mortar men, who tended to make it all the way through, while the infantry needed constant replenishment. I thought his, ‘welcome to the infantry,’ was a little flippant, considering it might mean a death sentence for me. I wanted to cry out, and say, ‘fuck you, man,’ but I couldn’t. It wasn’t his fault, anyway. The game for me now was taking it, whatever came down, to suck it up and take it. It’s what a man did, even though most of us were barely a step away from childhood.

The captain dismissed me with, “go see the supply clerk and get squared away.” I wasn’t sure what that meant other than show up, collect the implements of war and wait. I was well into my third day from Fort Lewis and I was angry, confused and scared, and now looking at a most uncertain future.

I found the company supply clerk a couple of tents over. He called me Cherry in his first sentence and a couple more times within the first minute. He was letting me know I wasn’t shit around here even though he was just a private and I outranked him.

Soldiers who were new to Vietnam were called Cherry because they immediately turned bright red with sunburn from the tropical sun. All skin shades suffered this indignity, even those who thought they were immune. That was the outward sign. For grunts in the field, being a Cherry meant you were untested in combat and might fuck up somehow and get somebody killed. A few months into my tour, a Cherry frantically threw a hand grenade during a fire fight, hit a tree in front of him and it bounced back in my direction. When it exploded, a tiny bit of shrapnel hit my inner thigh just below my left nut. I cried out with anger, and Lurch, the platoon sergeant rushed to me, whipped out his bayonet and before I could stop him, slit my trousers from my balls to my knees only to reveal a tiny wound that was barely bleeding. He said, “Shit, I thought you were really wounded.” I said, “Thanks a lot Sarge, for ripping my pants wide open.” We were in leech central and I could almost hear the dinner bell going off.

Cherries were often the first to die and nobody wanted to know their names or anything about them until they proved skillful or lucky enough to be around for a while. Loss was a mother fucker in this game and in order to lessen it, Cherries were brutalized, making them less than human until they faced their baptism of fire. We were a tribe and once in, you were a brother, loved and protected, and nobody wanted in more than a Cherry.

We were hard on one another too, rough humor at every chance, unflattering nicknames, jokes at everyone’s expense. We played it hard and fast as if nothing got to us, like we didn’t care about anyone. Of course, in the next instance, the butt of your joke would be trying his damnedest to keep you alive. It was always the tribe above all else. I think the rough and tumble made loss easier to bear. It hurt when a lucky one made it all the way through and got to go home, and it hurt when an unlucky one didn’t.

The clerk unlocked a metal gun cabinet and handed me a weathered M16 saying, “sign for it.” He shoved a clipboard at me and I signed He went on, “keep it clean Cherry,” meaning the rifle and handed me a cleaning kit. One of his jobs was supposed to be putting the rifles back in top working order when they were sent back from the field or turned in by a grunt headed home. The rifle he gave me was barely functional, the return action on the bolt being too slow and weak.

The M16 used gas from the just fired round to push back the bolt compressing a spring and allowing a new round to rise up from the magazine. The spring would then push the bolt forward catching the new round and shoving it into place. If there was any dust or grit inside the chamber or on the bolt, the spring often wasn’t strong enough to fully seat the next round resulting in a jam. It was a design flaw that a fifty cent better spring would have corrected, but I don’t think Colt gave a shit. They’d already been paid.

Early in my tour, I went through a couple of M16s because of jamming. I would request a new one be sent out on resupply day and return the poorly functioning one. Sometimes the replacement was in worse shape than the one sent in. The manual stated jamming could be avoided by cleaning the rifle regularly, ideally after every firing. There were no time outs in the field, no completely safe moments. We were in the middle of a jungle without front lines, just us and them quietly hunting one another. I never saw anyone clean their M16 in the field. We finally fixed the jamming problem ourselves by taking the spring out and stretching the shit out of it, making it stronger in compression. The stronger spring even upped the rate of fire considerably.

I asked the clerk if I could have a side arm too and he said they were only issued to officers or medics and If I wanted another gun, I could try to buy one on the black market. Many of us did just that, buying one through friends of friends and on the down low. We bought pistols and shotguns and anything we could find to have some back up. I bought a .22 caliber long round pistol. It was way too small for the job but it was all I could get my hands on and it was better than nothing.

It was easy to burn through a lot of magazines in a fire fight and running out off ammo wasn’t an unreasonable worry. Most grunts carried two bandoliers, I always carried three. For years after I got back home, I had odd nightmares about running out of bullets. The Freudians might say I was fearful of inadequate or declining sexual prowess but sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

The clerk pointed to a bag about three feet in diameter and said, “pick out your fatigues.” Inside was a mishmash of well worn pants and shirts of all sizes and various shades of green, reflective of numerous low bid suppliers. There were green socks and green boxers too. I went through half the bag until finding a full set that fit me well. In the field, the clean clothes bag would come out every once in a while and if I got to it late I’d wind up with pants three sizes too big and shirts two sizes too small and looking a lot like the Little Tramp for a few weeks.

I changed out of my dress uniform and shiny shoes, shoved them into my duffel and put on my brand new used clothes. The clerk took my duffel and filed it with all the others, to be retrieved by me a year hence.

He tossed me a ruck sack, which was an aluminum frame with a canvas bag hanging on it, circa 1952. He pointed at a tall stack of large cases marked C rations and told me to grab two and load up. A case held twelve individual boxes of different meals. Inside each meal box I found several green cans of various food types and a foil pack containing a five pack of Marlboros, a P38 can opener, a couple of chiclets, and a thumb sized pack of toilet paper. After that, he issued me six one quart canteens, five hand grenades, a Claymore Mine with clacker, two hundred rounds of M60 machine gun ammo on a belt, two bandoliers of M16 magazines, 250 rounds to go into the magazines, a couple of smoke grenades of different colors, four flares, an entrenching tool, a bayonet with scabbard, a 50 caliber water proof ammo can to store my personal gear in, a poncho, a thin quilt blanket in cammo colors and a steel helmet.

I had no idea what to do with all this crap and the clerk offered no help. He washed his hands of me saying, “secure all your gear Cherry. When you finish, the mess hall’s over there,“ waving a hand in no particular direction. I asked, “where do I sleep?” He replied, “back there,” jabbing his thumb over his shoulder as he walked out. He actually had a quitting time and I had kept him a few minutes past it.

It took me an hour to open all the little meal boxes and jam most of the cans into my ruck sack. It took another half hour to figure out where to put everything else but I finally got it all hanging from or stuffed into my pack. I put my arms in the straps and found I couldn’t get up off the floor with it. I rolled over onto all fours with the pack on my back and managed to stand up, the weight of the thing bending me far forward. There was no padding between the heavily loaded bag and my back and the cans of C rations dug in painfully. I had to go down on all fours again to get the damn thing off me.

An experienced grunt would have a pack that weighed around 80 lbs. fully loaded that would last him for about 8 days until the next resupply. It would get lighter as the week wore on. Weight was important because we spent twelve hours a days humping the things up and down mountains. I didn’t know any better and loaded up everything the clerk had given me and my pack probably weighed around 120 lbs.

No one, anywhere along the line during my year long training in the States, had mentioned anything about packing for the field, what to bring, what to leave out. No tips like carrying 2 fewer canteens to save weight, no helpful messages about cherry picking the C rations and leaving behind most of the box, no hint that 5 grenades were 3 too many or that one smoke grenade would do the job or 100 rounds of M60 ammo was heavy enough already. It should have been that lazy R.I.M.F., rear echelon mother fucker of a clerk to help me pack for the first time but then I was the new guy, the cherry and nobody liked cherries.

I left my newly packed ruck sack and rifle in the supply tent and located the mess hall where I had a blob of slop spooned onto my plate by a guy who looked like he wanted me drop dead or perhaps himself. I ate alone among a gaggle of RIMFs. I hadn’t seen a bathroom for quite a while and asked Mr. Drop Dead where I might find one. I think he was too stoned to talk and just pointed out the door. I hurriedly searched the neighborhood until I found a six stool plywood outhouse. It was raised a few steps to allow for one half of a 50 gallon steel drum to be placed under each of the six thrones. It wasn’t my first outhouse, having been a hippy in the late ‘60s but this was the industrial version of those Wisconsin farm house crappers. The half barrels filled up each day and some poor slob had to pull them out in the morning, pour in diesel fuel, light it and stir the shit with a wooden paddle until it was nothing but ash.

It was dark as I made my way back to the bunk area the clerk had pointed to. It was another wood and tent structure with about thirty empty cots in two rows. I had retrieved my gear from the supply tent and spent the next hour cleaning my rifle under the harsh light cast by a single bare bulb hanging from the ceiling. I had no experience getting the M16 rounds into the magazines and spent another hour struggling with that. I filled my canteens from a large billet of water I found just outside the supply tent. As far as I knew, I was ready to go. I had the large tent to myself as everyone else was out in the field. I unscrewed the light bulb and got a good nights sleep.

It was the early morning and the beginning of my fourth day from Fort Lewis when I revisited my experience with the mess hall. Mr. Drop Dead was there and whacked my plate with a mound of powdered eggs. After breakfast, I discovered that the crapper was even more aromatic in the morning than the previous evening and currently had only one vacancy. I took it. It was an enchanting morning but it was time to return and see about my orders. When I got back to the supply tent, the clerk said, “hey Cherry, follow me.” He walked me back to the crapper, lifted up a flap in the back and yelled. “hold your fire.” He pulled out a tub of shit and gave me instructions on how to burn and stir it. He pointed to a five gallon can of diesel fuel and handed me a book of matches. As he turned to leave I said, “I don’t take orders from privates, private. You fucking do it,” and handed the matches back to him. He had a hissy fit and ran off to get the captain. I slowly walked back toward the supply tent and found the captain and the clerk in conversation. The captain looked at me and then at the clerk and said, “sergeants and above don’t burn the shit, you do.” I had dodged my first bullet with a little RHIP, rank has it’s privileges.

The clerk slunk away and I turned to the captain, “sir, I’m having a problem with my pack. There’s no padding between the bag and my back.” He said, “oh christ, isn’t anyone helping you?” I said, “no sir, no one’s around except for the clerk,” cementing me forever on the clerk’s shit list. The captain told me to take the heavy cardboard box the C rations came in, double it up, trim off the flaps and loop it over the frame of the ruck sack so that it hung between my back and the cans. I did so and it solved the problem and I used that same hunk of cardboard for many months until it melted away during the monsoon rains.

Before the captain left he told me to finish up with the ruck sack, bring my gear and report to him at 0900 hours. When I showed, he told me to wait out front for a jeep that would take me to an LZ, where I was to get on a chopper. The jeep arrived, I struggled a little getting the ridiculously heavy pack into the back, got in and off we sped. The LZ was just more dirt with a heavy coat of diesel fuel to keep the dust down when choppers landed. There was nobody at the LZ to report to, but the driver leaned out and said, “just wait over there,” pointing to some other dirt with less oil on it.

I sat by the LZ for an hour or so until a chopper landed. I lugged my rifle and pack over to the open side of the Huey helicopter, ducking down from the rotor blades like I’d seen people do in the movies. I shouted over the roar of the engine, “Sergeant O’Meara.” The door gunner shook his head and shouted back, “next bird.” Two more birds came and went with the door gunners shouting the same, “next bird.” It had been several hours of waiting but the fourth bird told me to get on. I heaved my pack onboard and got in with it. I had no idea what was de rigueur for chopper riding. This was my first.

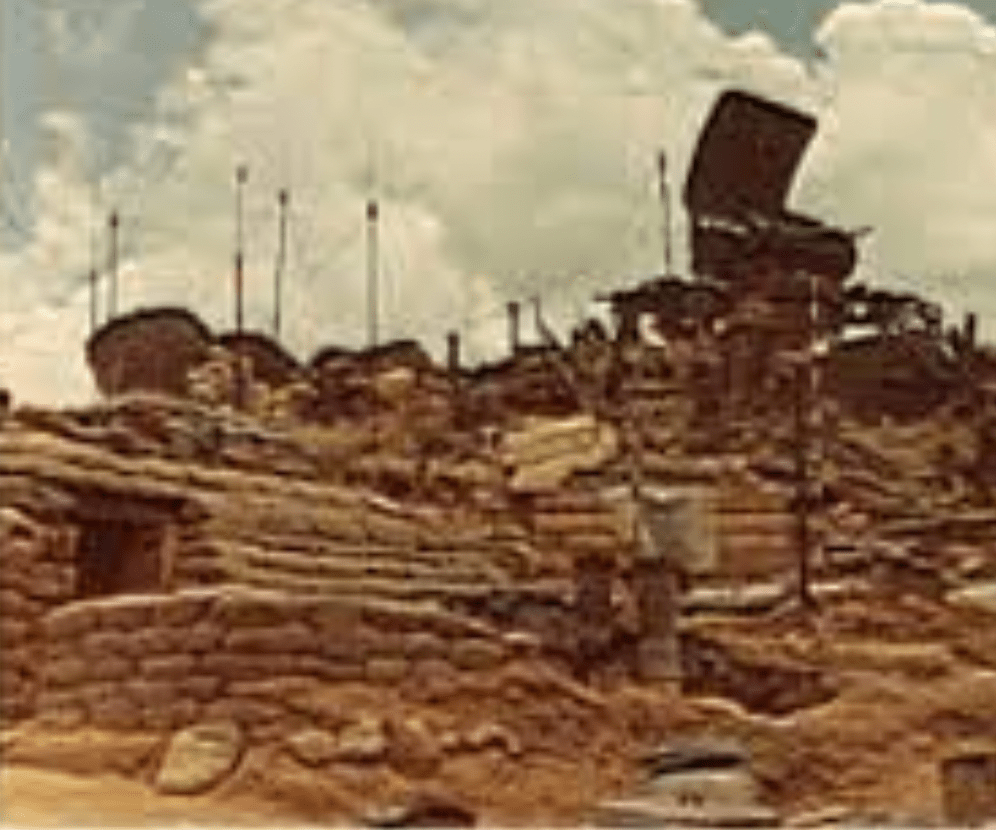

After a short flight we arrived at Fire Base Bastogne. The pilot squeezed the chopper in on a postage stamp sized LZ surrounded by high walls of sandbags. I thought, ‘man, this is some dangerous shit,’ little knowing that this was a cake walk for pilots compared to landing among the trees. I grabbed my pack and got off, as others were throwing in boxes of C rations, ammo, blivets of water, cases of sodas and bags of stuff. At the last minute, two grunts with packs on their backs got onboard. They sat with packs on, butts inside and legs dangling outside the chopper. I stood newly informed and corrected. I saw a guy with a headset talking into a radio and dropped my stuff by him and waited until he was free. I gave him my name and he flipped through some pages on a clipboard and yelled over the chopper noise, “Stay by the LZ, you’re going out soon.”

I found a spot only a few feet away where I could wait and maintain eye contact with Radio Man. It was too loud to hear him at a distance and I would have to rely on his hand signals to let me know which bird to get on.

I waited by that LZ the rest of the morning, through the afternoon and into early evening with a dozen or so choppers landing, but none of them for me. I dozed off occasionally, leaning on my pack, head on my chest until the roar of a chopper engine and a blast of hot exhaust would shock me awake.

When I got hungry or needed the latrine, I checked in with Radio Man to see if I could get away for that little bit of time. At dusk, he took his headset off and walked over to me and said, “That’s it for today. Don’t go anywhere, the first bird will be in at sunrise.” I spent the night right there, on that piece of dirt, next to the LZ.

My fifth morning since Fort Lewis started just after sunrise as predicted, with a Huey landing a few feet away from me, the prop wash tossing around the stuff I’d left lying about from the relative calm of the night before. Radio Man was back and was waving his arms excitedly and jabbing a finger at the LZ emphasizing some point he was making on the radio. I caught his eye and gave him a ‘me now’ look that he angrily waved off. When somebody in the military gets a case of the ass like that it’s best to let them work through it, and calm down before approaching. The bird left loaded with supplies, but no soldiers.

I gingerly approached Radio Man and asked, “Do you have any idea when I might be going out?”

In a surprise turn of mood, he calmly said, “Not sure at this time. Just wait where you are and I’ll let you know.” I think he had a moment of sympathy as everyone knew hurry up and wait was a pain in the ass.

It was another excruciatingly long day of waiting, not knowing if the next bird would be the one to deliver me into the heart of this horrible war. Each incoming chopper brought a wall of sound, a thumping pressure and heavy exhaust fumes, all of it starting to wear me down.

Dusk came once again and I was still sitting on that same piece of dirt. Radio Man was done for the day, which meant I was too. He walked over to me and said, “Hey man, let me see if I can get you a bunk.” I followed him to a fighting position at the perimeter of the firebase.

On the downhill side on all the bunkers, another name for fighting positions, were openings where soldiers could fire their weapons at anyone coming up the hill. Further downhill were rows of concertina wire that were meant to keep anyone from charging up the hill. Sappers were something to worry about. They were specially trained to cut the wire, slowly crawl up in the night and throw grenades or satchel charges into the bunkers.

Radio Man and I ducked our heads and went down into one of them. There were a few guys sitting around playing Monopoly and smoking pot. They hid the joint when we came in until they saw we weren’t officers. The joint passed to Radio Man and then to me. Radio man asked,” You got room for one more?” One of the game players pointed to an empty slab of wood and that was where I dropped my pack and lay down. I glanced at the game board but couldn’t tell if the hat, the race car, the bottle cap or the rock was winning. I must have fallen asleep right after that as the next thing was one of my new roomies waking me for my turn on guard duty.

While I was staring into the blackness for my two hours, the largest rat I’d ever seen joined me on my watch. I suspect these guys had been feeding it, because it sat there staring at me for fifteen minutes, before finally throwing in the towel and scuttling off.

With the sunrise it was six days since leaving Fort Lewis in Washington State. I returned to my familiar piece of dirt at the LZ with the thumping and the choking wind and thought, ‘just fucking bring it on already.’ I was still anxious as hell, but had reached that point where getting out of the now was preferable to not experiencing the next. I had no idea where I was headed, but knew with certainty it was going to be extremely dangerous. A year before, my sister Shelley had consulted a local clairvoyant and asked her if I would be okay and come home in one piece. She said I would make it home in one piece, but I would be a different person. Fairly safe prediction for a guy headed to war.

An hour or two after sunrise I could hear another chopper coming in. When it got close, Radio Man yelled at me and pointed, “Yo, get on that bird.” It came in sideways because of a stiff wind wanting to blow it away. It landed and immediately people were throwing boxes and bags and cartons on board. I put my heavy ass pack on, grabbed my M16, put my helmet on and made the short walk from my familiar piece of dirt to the open side of the Huey. I nodded at the door gunner and he nodded back. I got on, pack on back, butt inside, legs dangling out, just like the pros did it. The chopper lifted off and rose above the fire base. I wouldn’t see Bastogne again for eighty six days.

Leave a reply to kathy Cancel reply