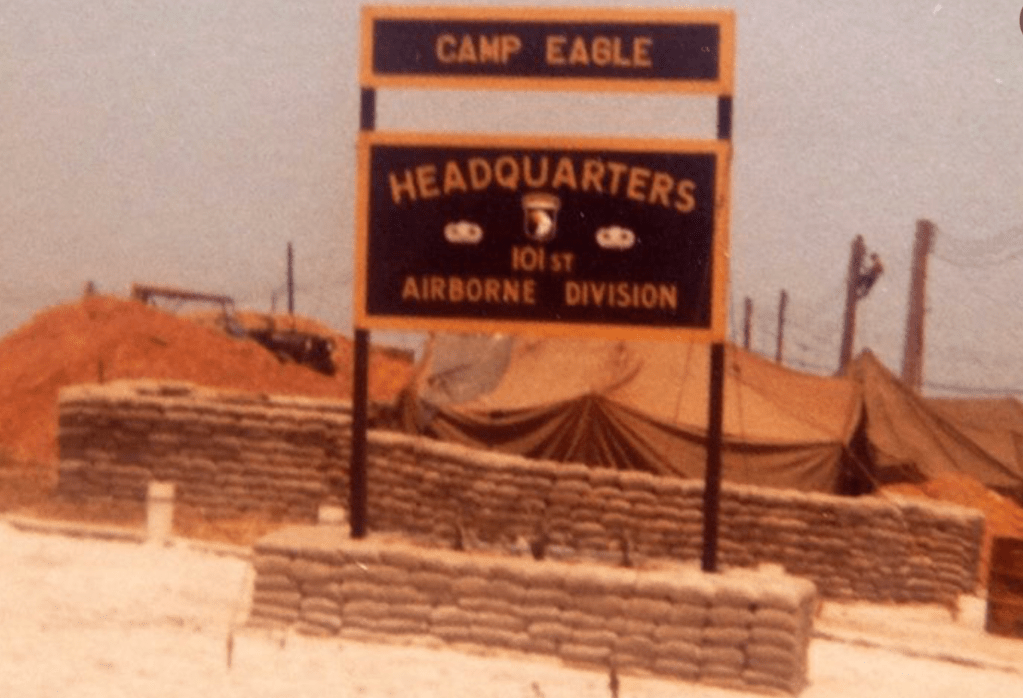

It had only been twenty-six hours since departing Fort Lewis and already I was standing by the side of a dirt airstrip in Camp Eagle, wondering what comes next. An hour later a jeep pulled up and a friendly looking guy said, “O’Malley?” I said, “O’Meara.” He said, “Get in.” The open air jeep looked like it had limped along from WWII, through Korea and was in the twilight of its service life, here in Vietnam. I threw my duffel in the back and got in. He drove like a maniac, taking turns where I swore the wheels left the ground.

I don’t know why, but everyone in the Army drove like the devil was on their tail. The Deuce and a Half drivers were the worst, tearing over the dirt roads in the indestructible two and a half ton, open air trucks. They transported anything and everything the Army had, including troops. They came with optional canvas tops and flip up metal seats on both sides. Whenever I had to ride in one, the first thing I did was find something to hang onto, certain it was going to be a bumpy ride.

Camp Eagle was the size of a small city, built by the Army Corps of Engineers. The makeshift structures were mostly OD (Olive Drab) tents, with some wood framing, and augmented with plywood and corrugated metal. They were ringed on all sides by sand bags stacked about ten high. Fifty years later, I rented something quite similar in Curry Village in Yosemite, sans sand bags.

The jeep bumped and jumped and swerved along the rutted twisty dirt road, on its way to C Company headquarters where I was to report. We drove for some time, the tiny engine screaming the whole way. If anything crawled, slithered or scurried onto that road, they’d better be quick or they’d be toast. Suddenly, the driver took a hairpin turn and skidded to a stop. “OK,” he said. I got out, thanked him for the lift and got my duffel out just before he spun the tires in the loose dirt and left me in a cloud of it.

C Company was another cluster of drab tents. They all looked alike, dusty, dilapidated and beaten down. There was no sign, that I could see, that said, ‘the big guy resides here.’ I moseyed around for a while until I ran into a stoned looking private. He knew right away what I was looking for, as I had arrived in my brand new khaki uniform and spit shined boots. He looked like he’d just spent his last two dollars at the Goodwill store and slept in a dumpster for two weeks.

The private pointed out where the Company Commander could be found. His tent had a tiny, hand painted sign, hanging slightly askew, that read, “Company C Commander.” His screen door was hanging by its last few screws. I knocked gently, trying not to bring the whole thing down, and a voice said, “Come.” I came. I straightened up in front of him, and with a snappy salute announced, “Sergeant O’Meara, reporting for duty, sir.”

The Company Commander was a captain, maybe in his early thirties, which made him a lifer. He seemed slightly bored, but interested enough in me to ask what my MOS was, meaning what was I trained in.

As the war was expanding, the military needed ever increasing numbers of troops. The first place they looked was in the penal system, offering early releases for joining up. The second place they threw the net was at colleges and universities.

In school, I had unwisely chosen to major in pot, beer and women and my grades reflected that. I had to maintain at least a 1.0 average to keep from being drafted and I had balanced my deferment needs with my debauchery needs rather nicely through my freshman year. However, in the first semester of my sophomore year, the government raised the necessary GPA level to 2.0 and in December 1968, I was just under that. My school immediately notified the local draft board, as they all did at that time, and a couple weeks later, the “Greetings” letter arrived.

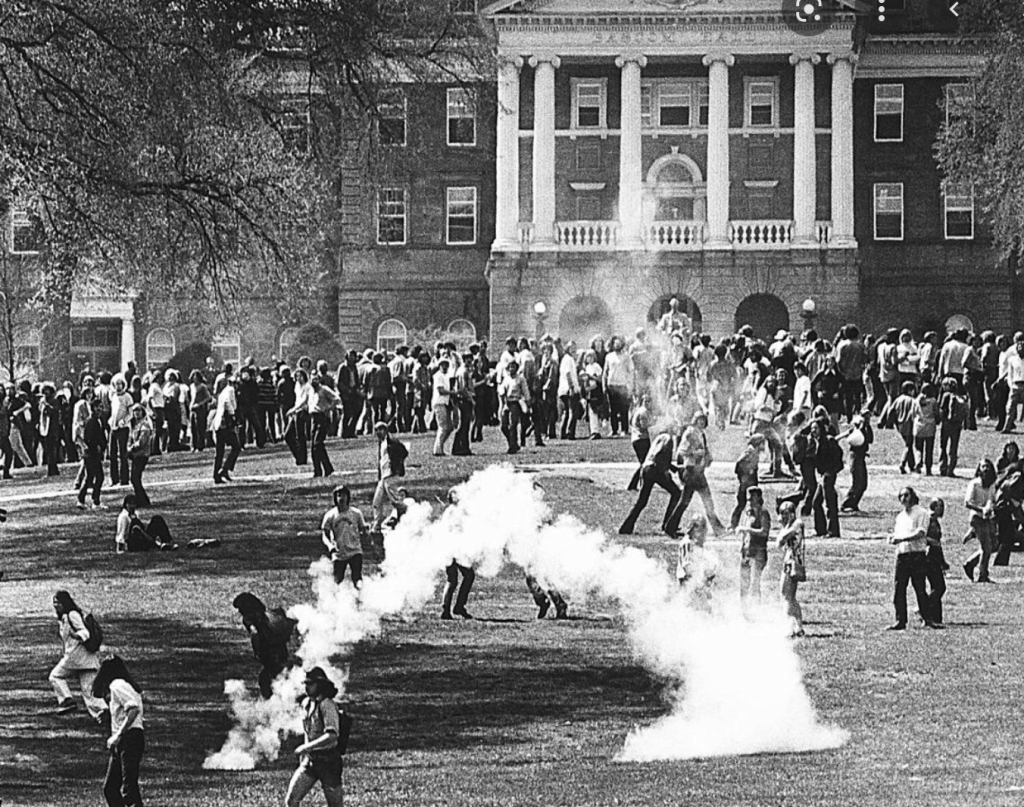

The war was still popular with most Americans in 1968, but on campuses students were protesting. In the summer of ’68, I was in the front of a group of several thousand protesters on the UW campus, yelling, “Back to Bascom Hall!” An undercover agent, from the COINTELPRO gang of criminals or the FBI, had taken the megaphone at the beginning of the protest and chanted, “Let’s take over the Ag Building,” until he had drummed enough support from the crowd to follow him there. The Ag building was a good place for the police to corner and disperse us. When it dawned on us that we had been duped, we were determined to return to Bascom Hall and the police were determined not to let us. They started coming at us with shields and batons at the ready. I took a few steps toward them, turned to encourage my fellow demonstrators onward and noticed I was all alone in the middle of the street. WMTV got a lovely shot of my head being whacked by a police baton, and it wasn’t even my good side.

One of the things that made me uncomfortable, talking about Vietnam, when I got home, was the unspoken question, why did I go. No one actually asked that, but it often seemed to linger somewhere behind the eyes. Before being drafted, whenever I applied for a job, the first question on the application was always, ‘are you a draft dodger.’ If I had decided to go that route, the penalty was ten thousand dollars and five years in a federal prison. If I ran, the penalty was the same, and it meant being a fugitive for the rest of my life. Every week the local news ran stories of some poor fellow found hiding in another state or country, who was being returned to stand trial.

Canada, bless them, was the only safe haven. The day before I was to report for my induction into the Army, my sister had all the money my parents could scrape together and was prepared to give it to me along with a one way ticket to Vancouver. They knew I was “on the fence” and wanted to support me, in case I decided to run. My parents had voted for Nixon and supported the war, but I was their only son and that was that. By the time I returned, my mother had changed parties and transformed into a Grey Panther.

I didn’t know anything about Canada and had visions of living above a hard goods store for the rest of my life, in a snowed under village with a moose strolling down main street. Altogether, it was too much and in the end, I didn’t have the balls to run for it.

Many years later I spent a week in Vancouver. I couldn’t help but think back to that decision I made so long ago and slowly came to the realization, ‘you dumb fuck, you could have been a Canadian!’

I was inducted in January 1969 in Milwaukee. As a last shot at freedom, when questioned, I told the induction guys that I had flat feet, high blood pressure and wet the bed every night. I think they’d heard that bullshit a thousand times and didn’t even bother with me and in I went. We were immediately loaded onto buses and driven to Fort Campbell, KY.

We arrived in the early morning, and were screamed off the bus by my first drill sergeant. He screamed at us to get in line for the mess hall, and screamed at us to hurry up and eat. A group of buzz cut soldiers, sitting at a table eating, saw my long hair and one of them made a comment about it. I shot back, “Eat your heart out, baby.” Not knowing anything about the Army, I had addressed the captain and was instantly surrounded and threatened by the group of enlisted men from his table. Amid all the yelling I said, “It’s my first day, give me a fucking break.” For some reason they all stopped. A couple of the assholes came by the barber shop later, just to watch me get shorn.

Everyone went through two and half months of Basic Training and the same amount of time for AIT (Advanced Infantry Training). I went to Fort Campbell first and then to Fort Polk, LA. During those five months, the Army gave us aptitude testing to see if we had any experience they could use. They had a lot of jobs to fill and wanted to match us up with them. My years of Esperanto and Latin really paid off for me here, as it was determined I had no skills whatsoever that the Army wanted or needed. The infantry is where they dumped the undesirables, misfits and college boys with no sensible skills.

At the same time, Nixon was stalling at the Paris peace talks over the seating and shape of the table, but there was some hope the war might end in six months, a year maybe. The aptitude testing determined I was smart enough to be offered NCO school, to become a Non Commissioned Officer, at Fort Benning, GA. It seemed like a good way to stay stateside for the five months the training would take and I accepted the offer.

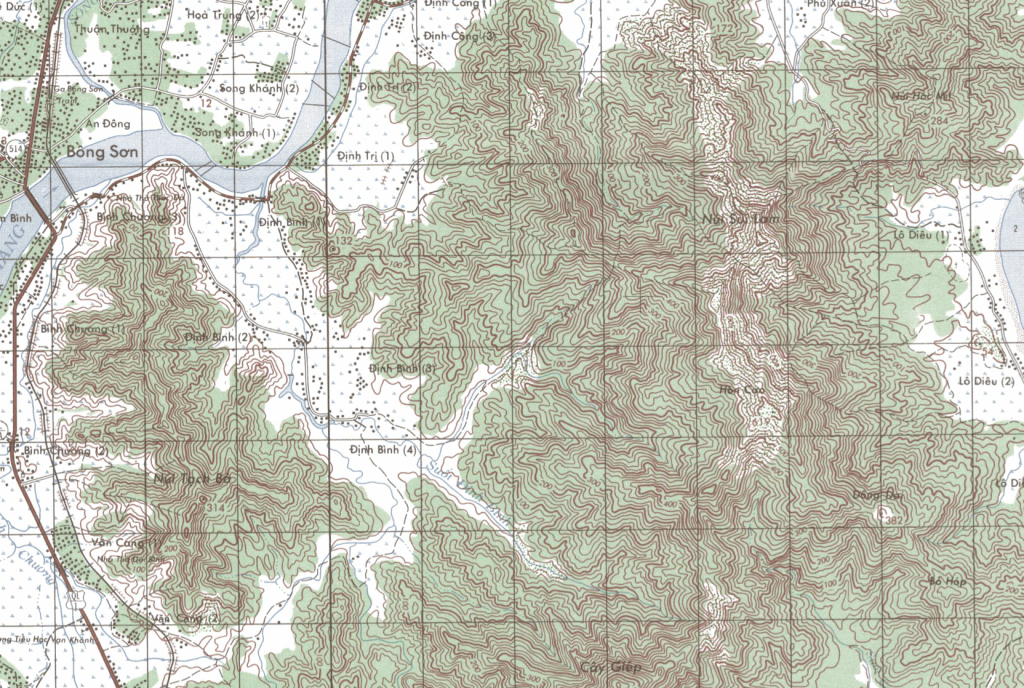

At Benning, I got lucky and was assigned to train as a mortar crew chief. Being in mortars meant being a resident on a fire base, and not a boonie rat, living in the bush. The classwork was moderately interesting and included extensive work with topographical maps and learning the language of indirect fire support. At the end of the training I was promoted to the rank of E5 sergeant, known as a Shake and Bake.

I was next assigned to Fort Ord, CA where I spent a few months teaching Advanced Infantry Training to the newbies. I bunked with a couple of other Shake and Bakes and had some freedom to come and go. I bought an old car and used it to drive into San Francisco to get drunk and buy pot. One weekend, deep in our cups, several of us jumped off the third floor balcony of the motel we were staying at and into its tiny pool. The management requested we leave, but we refused to go. Many decades later, I was walking along Van Ness Ave. and suddenly, there it was, the cheap motel with the crapping little pool, still alive.

When my time at Fort Ord was up, I was given new orders to report to 3rd Battalion, 1st of the 327th, Company C, Vietnam. A lieutenant colonel was in charge of the Battalion. His handle was “Bulldog,” and he and I would get along just swell over the next year.

In Vietnam, I was given the same topographical maps I had used at Benning. Out in the bush, I was one of the few grunts who could actually read the thing and figure out what part of the jungle I was standing in. To this day, I look at a topographical map and the landscape rises off the page in three dimensions. I also came over already familiar with calling in and adjusting artillery fire and air strikes. Both skills turned out to be most handy.

One of the things the Army did regularly, was to promise suckers who enlisted, they would not have to go into the infantry, but instead would be trained in some useful trade like truck mechanics and spend their time repairing vehicles in Germany. Most of my fellow grunts in Vietnam were draftees, but the few enlistees all sang the same sad song of betrayal.

The Captain, in the dilapidated tent, asked me for my orders. I handed them to him and volunteered, “I’m an 11C40, sir. Mortars.” I was thinking Camp Eagle wouldn’t be so bad, a tent, clean clothes, a cot, beer, women.

I asked, “Do you know which crew I’ll be stationed with?”

He wrote something on my orders, looked up and said, “You’re an 11B40 now. You’ll be heading out tomorrow. Welcome to the US infantry.”

« Visit the homepage to read more stories.

Leave a reply to Carolyn Cancel reply