I stood at what would fulfill the legal requirement of attention, but relaxed enough to let him know I wasn’t intimidated. He looked slightly older than my twenty years. A slim yellow bar stitched on both collars of his perfectly starched khaki shirt gave him legal authority over me, and compelled me to stand and listen to his drivel. He was thin and well kept, seemed intelligent with an air of university ROTC about him. He sat erect, hands folded in front of him on the green army issue metal desk.

With a practiced tone, he stated, “You are two weeks AWOL (Absent With Out Leave). I can put you in the stockade for this.”

My response, “Yes sir. Would that be in lieu of Vietnam?”

He glared at me for a moment and demanded an explanation for my tardiness.

I met Kathy when I came back to Madison for my month long leave before being sent over. It was wonderful being with a woman after nearly a year of intensive training. She was Italian, had long black hair, olive skin, and a face that was a sculptor’s dream. She was Catholic and had a four year old daughter, but had never married. We met at a bar and liked each other from the start. It was an intense romance that went on for my month’s leave and then a while longer. At first, I told myself, “I’m only a day late, surely they won’t mind.” A day turned into several and then a week and then two. When I couldn’t put it off any longer, a friend of my sister agreed to drive me to the airport. She was to pick me up early the next morning, at the apartment where I was crashing. I couldn’t sleep that night. Just before dawn, I started playing “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” over and over, and wept, from time to time. At 6:00 AM, my ride arrived. I slung my duffel over my shoulder, wiped away any trace of my boyhood tears, and said goodbye to the world.

Thirty years later, at a dinner party with some friends, a middle aged woman I’d known for a few years, passed me the joint that was going around and quietly said, “I don’t think you remember, but I drove you to the airport on your way to Vietnam.”

Two months after arriving in Vietnam, I was able to get a letter off to Kathy. It took weeks for her reply to make it out to me. I was in the mountainous jungle, just below the DMZ. When it arrived on a Huey resupply helicopter, I read it sitting on my steel helmet, sipping a hot chocolate, heated with a chunk of C4 explosive that burned quite nicely when lit. We moved location daily and about each week we would use the C4 to blow down trees to make room for a Huey to land, bringing us mail and the necessities of war. It was a short note from Kathy. In it she told me she was pregnant from our time together, and because of her religion, was going to keep the baby. She had met someone else, and said she was truly sorry, wished me well and goodbye.

I ran into Kathy three years later at a shopping mall in Madison. She was browsing a rack of clothes, our child in a stroller beside her. It was a boy. I bent down and quietly said hello to my son. She smiled, seeing a nice young man holding her son’s finger. Suddenly, her face turned a horrible shade of red, when she realized it was me. She grabbed the stroller and ran out of the store without a word. I followed her into the corridor and watched her disappear into the crowd. I never saw Kathy or my son again.

That young lieutenant, stationed at Fort Lewis just south of Tacoma, WA, didn’t see the wisdom of sending me to prison. I had been assigned to a gung ho outfit, the 101st Airborne Infantry, and he seemed to think that was punishment enough.

Fort Lewis was a shipping point for the thousands of young men going to Vietnam. I reported in to a clerk who told me to find an available bunk and wait for my name to be called, in a day or two. In the huge barracks, I milled around aimlessly like everyone else, our minds dulled by relentless waves of fear and confusion, akin to the cattle standing slack jawed in Niman Ranch holding pens, contemplating a grim future.

The bathroom stalls, at Fort Lewis, were covered with heartbreaking, last minute, goodbye notes to wives and girlfriends and parents and children, hundreds of them, crowded together, filling every little space. No puerile odes to scat or cheap shots at women, just these beautiful recordings of love, scratched into the dented, filthy, commode walls, in that old sad fort.

Two days later, my name was finally called with a group of others, and we were loaded into an army bus and driven to the Seattle airport. It was a twenty hour flight from Seattle to Vietnam, with a stopover in the Philippines, at what used to be Clark Air Force Base. I was flying in a Pan Am passenger jet, the unofficial airline of the CIA, with stewardesses and a couple hundred other GIs. We drank and chain smoked, and introduced ourselves with stories of who we used to be, and spoke of who we hoped to be on return.

The Pan Am plane came into Vietnam high, to avoid small arms fire. Once within the safety of the airport at Saigon, it banked sharply and dove toward the landing strip. Out the window, I could see the land passing beneath. Everywhere and in all directions were huge craters like the surface of the moon.

On arrival, the stewardesses flashed us lovely smiles and wished us luck. I got off the plane and was immediately slapped in the face by the wilting heat of the tropics. A Deuce and a Half took me to another part of the airport, where I was processed and told to wait. After hours of sitting on my duffel bag, someone called my name and pointed at a C130 cargo plane taxiing up and told me to get on it. I asked an airman, standing at the back of the plane, where we were going. He had a headset on, moved the microphone away from his mouth and, over the roar of idling engines, yelled, “Camp Eagle.”

Camp Eagle was the main base of the 101st Airborne, 82nd Airborne, and the 1st Cavalry Divisions. It was a large flat piece of land, bulldozed of all vegetation, and so heavily sprayed with Agent Orange that nothing grew back. The C130 landed on a short dirt strip, kicking up dust and debris. The base was surrounded by rows of concertina wire and fighting positions, and was relatively safe with only an occasional pounding from mortar rounds, or a rare attack by North Vietnam Army foot soldiers.

It was a sprawling base that warehoused and dispersed all the supplies needed to run the war in the Northern Highlands. It was a helicopter war and supplies were sent by chopper, from Camp Eagle, out to various fire bases dotted around the jungle. From the fire bases, resupply was sent out weekly, to the infantry in the field. It was also an artillery war and the infantry needed fire bases to be within mortar and Howitzer range of where they operated. If the army wanted to move into a new area, they would send the infantry in to secure a nearby mountaintop, bulldoze it, spray it, ring it with wire and claymore mines, and bring in the artillery and support personnel.

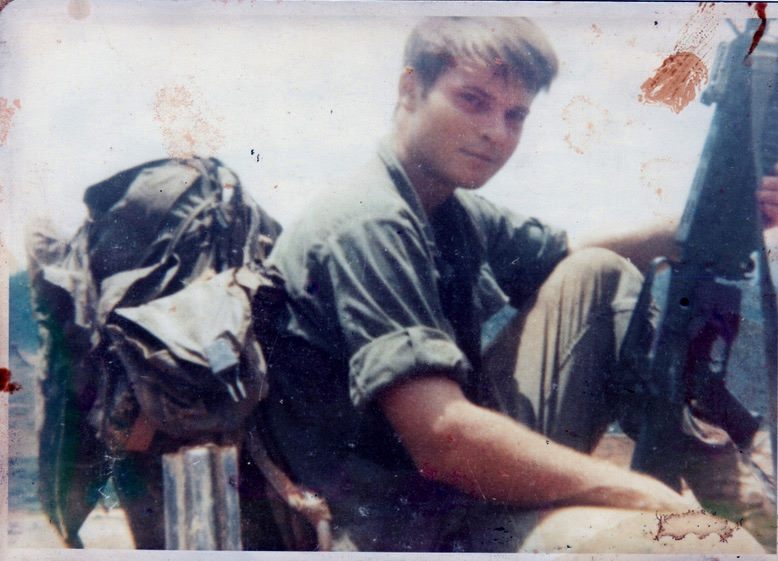

The infantry is only about fifteen percent of the army. All the other soldiers kept the machinery running; truck drivers, pilots, supply clerks, cooks, police, construction workers and so on. The lucky folks who lived at Camp Eagle slept on cots, in barracks, had stereos, beer, ate in mess halls, had clean clothes, regular mail from home, showers, women from the nearby town, no guard duty, and a much better chance of returning home in one piece. The infantry grunts, as we were called, led slightly different lives. We were left outdoors, in the jungle, in the wet and the cold, like an unwanted pet. We slept on the ground, without tents, got wet when it rained, roasted when hot, were always sleep deprived from sitting guard two hours every night, didn’t bathe or brush our teeth for months at a time, ate canned horse meat from Australia, crapped in the woods, carried eighty pound packs up and down mountains twelve hours a day, kept countless numbers of leeches well fed, and had people trying to kill us, at every opportunity.

Bulldog, the battalion commander, would let us come out of the field every month or two, and spend a couple of days on one of the fire bases. While there, we manned the fighting positions surrounding the bases and provided security for the residents. The fighting positions were holes dug in the dirt, with large wooden beams over the top and a layer or two of sand bags covering the whole works.

There were huge rats on the fire bases and their favorite thing was to jump into a fighting position and land on us, as we slept. Maybe they got a kick out of hearing us squeal, or maybe it was all about the food. They’d tear a hole in our packs, take out a can of C rations, and bite right through the metal. It was such a relief to get out of the field, that we really didn’t mind the little fuckers so much, as long as they left the canned peaches alone.

The residents didn’t mix it up with us grunts much. They avoided us, for the most part, I think, because they believed we were dangerous and bat shit crazy, and perhaps they were right.

Leave a reply to Carolyn Cancel reply